Self-compassion

Although there is still a need for more large-scale randomized controlled studies, self-compassion is recognized as a key positive psychology intervention for managing chronic pain (Mistretta et al., 2022).

By cultivating self-compassion, clients with chronic pain can reduce self-criticism and feelings of inadequacy (Edwards et al., 2019). This will improve their ability to navigate the challenges of living with chronic pain with greater ease and acceptance.

Resilience

Researched resilience-based interventions for chronic pain management involve (Goubert & Trompetter, 2017):

- Strengths identification

- Optimism cultivation

- Mindfulness

- Social support enhancement

- Meaning making

- Goal setting

All these interventions will build resilience, reduce emotional distress, and enhance overall wellbeing.

Humor

Using humor as a positive psychology intervention for chronic pain can offer numerous benefits (Ruch & Hofmann, 2017).

Humor shifts the focus away from pain, and it is a natural coping mechanism that provides emotional relief (Pérez-Aranda et al., 2019). Humor further assists with the management of chronic pain in that it fosters social connection, strengthens relationships, and provides emotional support (Finlay et al., 2022).

Gratitude

Practicing gratitude involves intentionally expressing appreciation for what you have, despite the presence of pain. Research suggests that cultivating gratitude can enhance psychological wellbeing, reduce stress, and improve coping with adversity, including chronic pain (Shah, 2021).

By making use of gratitude interventions, such as keeping a gratitude journal or writing letters of appreciation, attention is shifted away from pain and positive emotions are promoted (Boggiss et al., 2020).

Strengths identification

Identifying personal strengths and resources can empower individuals to leverage their strengths in managing pain and face challenges more effectively (Graziosi et al., 2020).

Strengths-based assessments and interventions can assist clients in identifying their own strengths and using them to better cope with chronic pain.

Social connection

Strengthening social connections and seeking support from friends, family, or support groups can provide emotional comfort and practical assistance in coping with pain (Sturgeon & Zautra, 2016). Positive psychology interventions that encourage social interaction and support lead to the development of stronger social support networks and improve wellbeing and quality of life (Farr et al., 2021).

Psychological capital

Psychological capital, comprising hope, optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy, may offer an effective positive psychology intervention for chronic pain management (Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, 2017).

Interventions that promote psychological capital aim to improve psychological wellbeing, enhance coping skills, and increase clients’ ability to thrive despite their pain.

It’s important to note that while these interventions are an integral part of a comprehensive pain management plan, they may not directly alleviate physical pain. They may improve psychological wellbeing and coping skills, ultimately enhancing the overall quality of life for individuals living with pain.

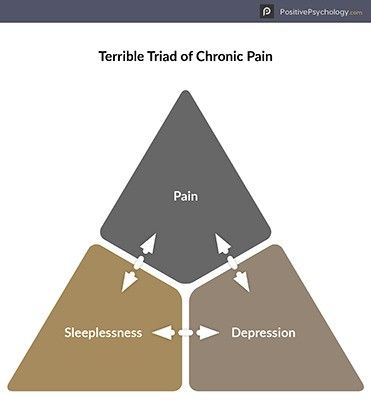

Chronic pain is a condition that causes widespread, constant pain and distress and fills both sufferers and the health care professionals who treat them with dread.

Chronic pain is a condition that causes widespread, constant pain and distress and fills both sufferers and the health care professionals who treat them with dread.