Introvert vs Extrovert: A Look at the Spectrum & Psychology

The concept of extroversion isn’t new, under one heading or another, theories of extroversion/introversion have been apparent in psychological literature for over 100 years.

The concept of extroversion isn’t new, under one heading or another, theories of extroversion/introversion have been apparent in psychological literature for over 100 years.

Many theories incorporate an individual’s level of extroversion/introversion as a key factor underpinning personality.

Extroversion plays a role in mediating how a person tends to direct their energy, that is, externally or internally and the level of extroversion can help us to understand how an individual is likely to respond to and interpret external stimuli.

How extroverted we are can have a huge bearing on our day-to-day life across a multitude of contexts and it’s important to note that there’s no ‘better’ level of extroversion/introversion – both ends of the spectrum have their advantages and disadvantages but by understanding where we fall on the scale we can address areas in which we’re perhaps lacking.

Understanding how introverted or extroverted an individual is can also help practitioners in the positive psychology space adapt their approach to suit the subject while in relationships and social bonds, knowing an individual’s propensity to internalize or externalize actions can help us adapt our behavior accordingly.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

- What is an Introvert, Extrovert, and Ambivert?

- What is the Introvert-Extrovert Spectrum?

- Introvert vs Extrovert: The Difference Between Personalities

- Is there a Difference in the Brain?

- A Look at the Psychology and Theory

- What Do The Statistics Say?

- 11 Interesting Facts

- Carl Jung’s Work on the Topic

- Other Introvert-Extrovert Tests, Scales, and Quizzes: A Look at the Validity

- Introvert and Extrovert Relationships

- 5 Recommended Books

- 5 Interesting TED Talks

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What is an Introvert, Extrovert, and Ambivert?

The early 1900s was a period in which the field of psychology was developing as an independent discipline. During this time, Carl Jung proposed core ideas in his exploration of personality, including the constructs of introversion and extroversion.

Jung (1921) suggested the principal distinction between personalities is the source and direction of an individual’s expression of energy – defining extroversion as “an outward turning of libido” (para.710) and introversion as “an inward turning of libido” (para. 769).

The interest of the introvert is directed inwards; they think, feel, and act in ways that suggest the subject is the prime motivating factor. Extroverts, on the other hand, direct their interest outwards to their surrounding environment; they think, feel, and act in relation to external factors rather than the subjective.

Consider a busy social event, an extrovert will likely revel in the social interactions and be invigorated by it, while an introvert will likely find their energy depleted and need time alone to compensate.

Not to be confused with Freud’s theory of the libido (1920) in which libido was described as a source of psychic energy specific to sexual gratification, Jung referred to libido as motivational to a range of behaviors – not solely sexual gratification.

Abernethy (1938, p. 218) defined an extrovert as “one who enters with interest and confidence into social activities of the direct type and has little liking for planning or detailed observation.” Conversely, introverts were defined as being “below the general average in social inclination and above the average in liking for thought.”

Introversion and extroversion are, in some ways, at the ends of the bell curve. So what lies between the two? Jung (1921) accepted there is an extensive third category and admitted it is difficult to determine whether this group’s energy comes from within or without, rather it appears to be drawn from both in varying degrees along the introvert-extrovert spectrum.

Heidbreder (1926, p. 123) suggested that “pronounced introversion and pronounced extroversion merely represent extremes of behavior, connected by continuous gradations. In other words, the evidence points to a single, mixed type rather than to two sharply separated classes.”

Conklin (1923) also posited the existence of ambiverts, considering them to be the most ‘normal’ with individuals showing flexibility between the two extremes. Roback (1927, p. 123) agreed that the majority who lie within this category are “the less differentiated normal man, the source of whose motivation can scarcely be determined offhand, as his introversion or extraversion is not sufficiently accentuated.”

What is the Introvert-Extrovert Spectrum?

Some things in life can easily be categorized. Eye-color, whether someone is left or right-handed, species within a genus, time-zones – these are all examples of discontinuous traits. With regards to the introvert/extrovert archetypal distinction, does human behavior really fall neatly into one of two categories?

In reality, most of us exhibit qualities of both and fall somewhere between the two. Rather than existing as a clear cut label, extroversion is regarded as a spectrum with individuals exhibiting a range of behaviors associated with both.

The Introvert-Extrovert spectrum, like many continuous dimensions within psychology, represents a way in which we can classify something in terms of its position on a scale between two extreme points. In this case an individual’s innate tendency to respond to stimuli in a certain fashion.

Considering the bell-curve of normal distribution for continuous traits, if we place absolute extroversion at one end of the scale and the absolute maximum tendency towards introverted behavior at the other we have a spectrum which can account for introverts, extroverts and every nuance in between.

When considering continuous traits, it’s important to remember that the invention of the dichotomous paradigm of introversion versus extroversion is a purely human imposition – aimed at providing a simple framework through which to categorize individuals based on their behavioral characteristics.

In reality, a spectrum provides a scale against which we can more accurately determine just where someone falls in terms of their behavior relative to others. While it’s easy to say an individual is either an extrovert, introvert or ambivert based on personality assessments, in reality, the multi-faceted nature of all behavior and the underlying contributors make such an assessment something of a broad-brush approach.

The human brain remains the most complex structure in the known universe. With 100 billion neurons, ever-fluctuating neurochemical levels alongside inheritable and learned components of behavior and not to mention dynamic stimuli as we move through life, our characteristics are much more complex than the binary or ternary intro/extro/ambivert distinction suggests.

Chair of the Psychology Department at Northwestern University, Dr. Dan McAdams (2017) described extroversion-introversion as a continuous dimension, suggesting there are no pure types in psychology.

As with other continuous scales like height and weight, there are of course people who score at the extremes, like very heavy people, or very tall people, or people who score very high on the trait of extroversion, but most people fall in the middle of these bell-shaped curves.

While the binary or ternary distinctions provide a broad-brush way to categorize individuals, the spectrum provides a much more accurate relative picture. Consider two individuals who complete a personality assessment including a measure of extroversion, for example, the Myers Briggs Personality Inventory (MBIT).

One receives an extremely high score for extroversion while the other scores mildly extroverted – is it fair to say they are both extroverts?

Introvert vs Extrovert: The Difference Between Personalities

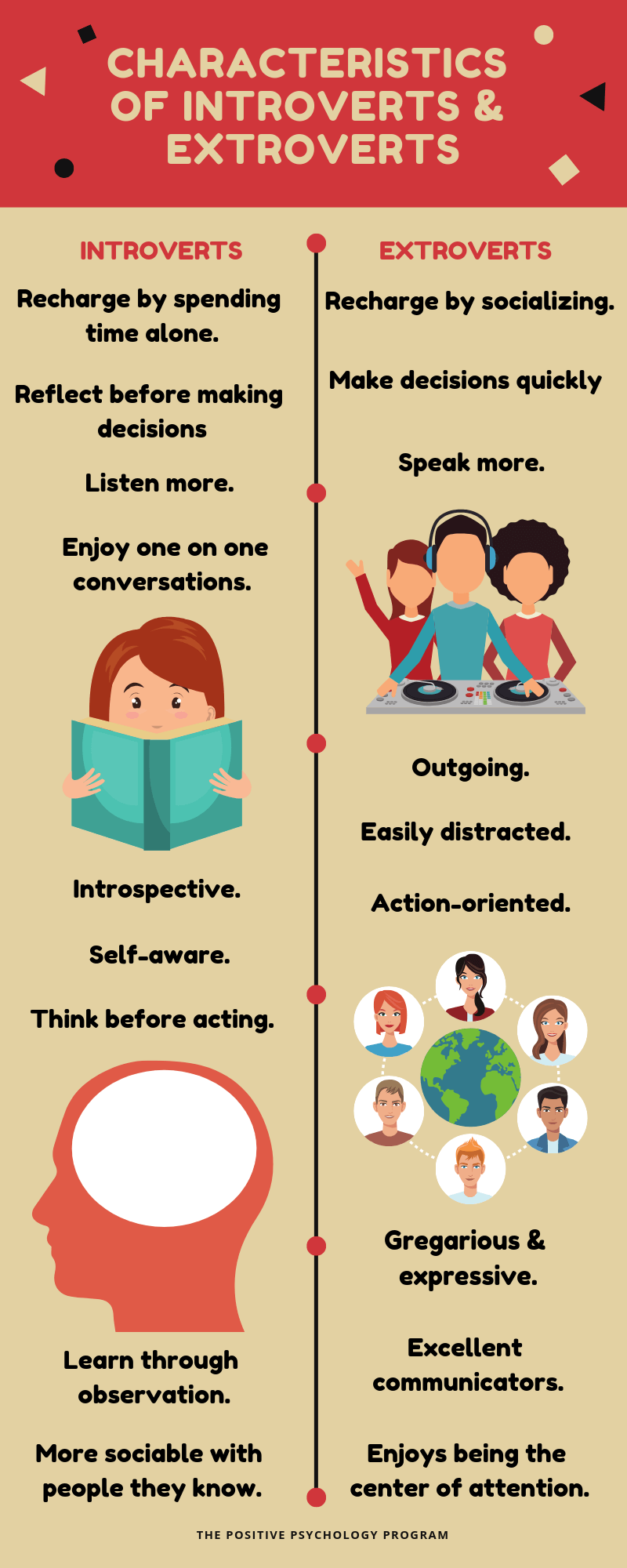

Assumed to be dichotomous halves of the introversion-extroversion personality dimension, introverts are considered to be reflective, private, thoughtful individuals while extroverts are thought to be gregarious, assertive, adaptive, happy individuals with a tendency to take risks.

Introversion and extroversion are complex, multi-faceted personality constructs. Individuals can fall at the extremes of each dimension or, more commonly, lie somewhere in between the two and exhibit traits of both.

Let’s have a look at a sample of introvert-extrovert personality differences in relation to the following areas.

Sociability

In social situations, extrovert and introvert personalities display very different behaviors. Extroverts show a preference for seeking, engaging in, and enjoying social interactions, whereas introverts tend to be reserved and withdrawn in social settings – often preferring to avoid social situations altogether.

Guilford & Guilford (1936) proposed two extremes of sociability: social withdrawal and social dependence. While introverts tend to be quieter, gaining enjoyment from spending time alone, extroverts are more socially-present, thriving on the energy of those around them, often finding themselves the center of attention in large social groups.

This is not to say that introverts are anti-social, rather they gain enjoyment away from the overwhelming stimulation produced by social gatherings.

Communication

Min Lee & Nass (2003) postulated the cause of the extrovert’s strong social presence is their tendency to talk more often and in louder voices, to take up more physical space with broader gestures and to initiate more conversations than introverts.

In a small study of students, it was found that during conversations with an unknown person, extroverts made more eye contact and spoke more frequently than introverts (Rutter, Morley, & Graham, 1972).

Additionally, extroverts are significantly more confident and accurate when interpreting the meaning of nonverbal communication than introverts (Akert & Panter, 1988). Termed ‘the extrovert advantage’ this nonverbal decoding was attributed to extroverts’ experience in social settings and their greater desire for sensory stimulation.

Decision-making

In time-pressured situations, introverts are more likely to use early information to form judgments and make decisions than extroverts in the same context (Heaton & Kruglanski, 1991).

Research into the impact of extroversion/introversion on decision-making suggested extroverts make more snap decisions based on what feels most natural at the moment. While extroverts were found to exhibit quality checking behavior before making decisions, there was also a need for someone to steer them in the right direction when they faced important decisions.

Conversely, introverts avoid impulsive decisions through thoughtful consideration, intuition and primarily count on themselves. (Khalil, 2016).

In the workplace

Extraverts generally hold more positive evaluations of life in general and their careers are no exception. Research has shown positive associations between extraversion and career satisfaction. Additionally, extroverts are more likely to take action in order to remedy unsatisfactory workplace situations than their introvert counterparts (Judge, Higgins, Thoresen, & Barrick, 1999).

Noise distractions in the workplace are more of a problem for introverts than for extraverts. Belojevic, Slepcevic, & Jakovljevic (2001) found that the introduction of noise distraction caused pronounced concentration problems for introverts, while extroverts actively selected higher noise intensities.

These results supported the hypothesis that introverts have a more pronounced reaction to noise, leading to heightened arousal which then interferes with performance on complex tasks (Eysenck, 1982).

Is there a Difference in the Brain?

Early research in the area of extroversion and introversion was predominantly anecdotal and self-reported. However, with the development of neuroimaging technologies, we have been granted access to a whole world of scientifically-supported, quantitative evidence that suggests the brains of extroverts and introverts really are different.

Research by Fischer, Wik, & Frederickson (1997) investigated neural differences in the introvert-extrovert spectrum by looking at regional cerebral blood flow. Their findings suggested a dopaminergic basis for individual differences in extraversion. In introverts, activity in the putamen was left-lateralized, with these areas having high concentrations of dopamine terminals.

Additionally, introverted subjects displayed an increase in neuron activity within brain regions associated with learning, motor and vigilance control. As such, it was suggested that extroversion is subcortical, neostriatal and dopaminergic, rather than solely cortical.

Lei, Yang, & Wu (2015) employed neuroimaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI) to investigate personality traits from a neurobiological perspective.

The results indicated that extraversion is associated with activations in regions of the anterior cingulate cortex (related to decision-making and socially-driven interactions), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (executive functions such as working memory and cognition), middle temporal gyrus (semantic memory and language), and the amygdala (processing emotions).

MRI has also been used to examine automatic brain reactivity as a function of extraversion. Eysenck (1967) suggested that, due to differences in the baseline activity of ascending reticular pathways, extroverts have a lower baseline level of cortical arousal than introverts. Cortical arousal increases wakefulness, motivation, attention, and alertness.

From this perspective, it is postulated that extroverts are minimally aroused and so will search for additional external stimulation in order to raise their cortical arousal level. MRI results found that introverts displayed heightened responsiveness within the frontostriatal-thalamic circuit (responsible for the mediation of motor, cognitive, and behavioral functions within the brain) when presented with sad, happy, and neutral facial expressions.

It was thus surmised that the presence of arousing stimuli – such as facial expressions of emotion – underpinned introverts’ preference for avoiding social interactions (Suslow, Kugel, Reber, Dannlowski, Kersting, Arolt, Heindel, Ohrmann, & Egloff, 2010).

Investigations into cerebral blood flow and introversion/extroversion sought to outline the areas of the brain associated with each dimension.

It was suggested that, while extroversion is significantly correlated with the anterior cingulate gyrus (emotion and behavior regulation), the temporal lobes (sensory input), and the posterior thalamus (regulation of sleep and wakefulness); introversion is associated with increased blood flow in the frontal lobes (involved in initiation, impulse control, and social behavior) and in the anterior thalamus (sensory signals) (Johnson, Wiebe, Gold, Andreasen, Hichwa, Watkins, & Boles-Ponto, 1999).

A Look at the Psychology and Theory

As early as 300 BCE Greek thinkers and physicians like Theophrastus tentatively pondered human behavior and characteristics. By the late 1700s, philosopher and scientist, Immanuel Kant discussed human personality in terms of four very distinct temperaments:

- Sanguine (carefree and hopeful),

- Choleric (proud and hot-headed),

- Melancholic (anxious and thoughtful), and

- Phlegmatic (reasonable and persistent).

In the realm of psychology, human personality has been the subject of great interest even before Freud first examined human behavior in relation to personality components.

While theories of personality encompass various aspects of human personality, the dimension of extroversion-introversion was a key factor in the development of each theoretical framework.

Popularized by Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung (1921), the terms extroversion/introversion were used to describe aspects of human personality as part of a collective unconscious. Jung regarded extroversion and introversion as the major orientations of personality. In the years that followed, many researchers developed and utilized methods of factor analyses that gave support to Jung’s initial distinction and built theories upon its foundation.

Eysenck (1967) assumed that brain processes could be characterized by means of a simplified conceptual nervous system that encompassed the key circuits relevant to personality and behavior.

Eysenck’s theory of personality (1967) identified two primary brain systems as the key components of his conceptual nervous system: reticulo-cortical (controls the cortical arousal generated by incoming stimuli) and reticulo-limbic circuits (controls response to emotional stimuli).

In this theory, levels of extraversion are directly related to arousal of the reticulo-cortical circuit through external stimulation, so that introverts exhibit higher levels of base arousal than extraverts. Eysenck went on to develop the PEN model of personality, a hierarchical taxonomy based the super factors of psychoticism, extroversion, and neuroticism.

The theory is based on the assumption that we have an optimal level of arousal and that as one becomes more or less aroused than their optimal level performance will deteriorate.

Cattell (1965) considered personality as being much more complex than previously theorized, and thus developed 16 personality factors ranging from extroversion (described as social boldness) to emotional stability. It was argued a much larger number of traits should be considered in order to garner a detailed understanding of human personality.

By the 1990s Digman had popularized the five-factor model of personality (FFM). The FFM is a set of five broad trait dimensions:

- openness to experience,

- conscientiousness,

- extraversion,

- agreeableness, and

- neuroticism.

Often referred to as the “Big Five” or O.C.E.A.N., the FFM was developed to represent the variability in individuals’ personalities as much as possible, using only a small set of trait dimensions. Many personality psychologists agree that its five domains capture the most important, basic individual differences in personality traits and that many alternative trait models can be conceptualized in terms of the FFM structure.

What Do The Statistics Say?

If you were to search for statistics relating to extroversion and introversion, you would be met with contradicting information and no real idea of what the true statistics say. Depending on the source, you may well find yourself facing a multitude of facts and figures that are quite simply unverifiable.

However, there are quantifiable statistics out there. Let’s have a look at some of the evidence-based statistical information related to the introversion-extroversion spectrum. It is important to note that many statistics in this area do not include ambiversion as a stand-alone trait, rather they acknowledge extroversion and introversion alone.

- The first official random sample by the Myers-Briggs organization showed introverts made up 50.7% and extroverts 49.3% of the United States general population. Myers, McCaulley, Quenk, & Hammer (1998) found that within this sample 45.9% of males and 52.5% of women were extroverted and 54.1% of men and 47.5% of women were introverted.

- A later study by the American Trends Panel (2014) utilized a five-point scale with which 3,243 participants described themselves as being closer to extroversion or introversion. Along the scale, it was found that 12% described themselves as very extroverted, while 5% considered themselves to be very introverted. 77% of respondents described themselves as falling somewhere between the two extremes. The remaining 6% were unsure and not included in the results.

- Freeman (2008) looked at how extroversion differed in American students and students from Singapore. The results indicate that Singapore students are less introverted (51%) than their American counterparts (62%).

- In a survey of 3,014 American lawyers, it was found that a majority 56.4% were introverts and the remaining 43.6% were extroverts. These figures indicated that extroversion/introversion is important depending on the area in which a lawyer practices. For example, labor law attracted the greatest number of extraverts, while real estate law and tax work seem to draw more introverts (Richard, 1993).

- Scherdin (1994) surveyed 1,600 librarians using the MBTI. It was hypothesized that librarians as a group would be logical problem solvers, working out solutions in their heads and independently and not loudly and collaboratively. The results found that 63% of librarians were indeed introverted while 37% were extroverted.

- 50% of extroverts make snap decisions and quick decisions, while 79% of introverts rely on their intuition and inner feelings (Noman, 2016).

11 Interesting Facts

- Introverts are more likely to locate their “real me” (the essence of who they really are) on the Internet, while extroverts locate their “real me” through more traditional social interactions. Amichai-Hamburger, Wainapel, & Fox (2002) emphasized the importance of expressing the “real me”, describing it as a crucial life skill. Those who cannot express their “real me” are prone to suffer from serious psychological disorders. It is thought that the social services provided on the Internet represent an avenue for introverted personalities to form social contacts.

- Heavy social media users (those who spend more than two hours daily) are seen by themselves and others as more outgoing and extroverted (Harbaugh, 2010).

- Introverts and extroverts respond differently to types of workplace training. O’Connor, Gardiner, & Watson (2016) revealed a relationship between levels of extroversion and training type – specifically ideation skills training (focusing on idea generation) vs. relaxation training (focusing on opening the mind and removing mental barriers). Their study suggested relaxation training is particularly beneficial for introverts whereas ideation skill training is more effective for extroverts.

- Extroverts are more likely to prefer immediate rewards. Hirsh, Guindon, Morisano, & Peterson (2010) suggested that extroverts are particularly sensitive to impulsive, incentive-reward-driven behaviors and are more likely to be involved in extreme sports and other risk-taking behaviors.

- When interacting with synthesized voice-mediated human-computer interfaces and VR systems we prefer synthesized extrovert/introvert voices that suit the context. Min Lee & Nass (2003) suggested individuals feel stronger social presence when stereotypically introverted roles are represented by an introverted computer voice, in a library for example, rather than when they are represented by an extroverted voice. In situations where socially present virtual actors are desirable, in sales and marketing, for example, selected voices should clearly manifest extroversion.

- Introverts and extroverts prefer different leisure activities. Diener, Larson, & Emmons (1984) suggested extroverts are more likely to participate in social leisure activities. Conversely, introverts are more likely to participate in solitary leisure activities.

- Extroverts and introverts have very different verbal styles. Beukeboom, Tanis, & Vermeulen (2012) investigated the link between extroversion and language abstraction, they discovered that extroverts tend to talk in more abstract terms whereas introverts are more likely to focus on concrete facts.

- Extroverts are more likely to be achievement oriented and have learning styles that promote group activities. Codish & Ravid (2014) examined the personality trait of extroversion and how individuals with high levels of extroversion and introversion perceive different game mechanics in a gamification setting (the application of gaming elements, such as a point system or leaderboard, in other activities). Their findings suggested that extroverts prefer talking out loud, and learning through interactions. Introverts on the other hand prefer to reflect first and act later, work privately and present their work in a way that lets them keep their privacy, preferring intermittent communication rather than a constant flow.

- Ambiverts tend to perform better on IQ tests. Research into the relationship between intelligence test performance and personality dimensions suggest that the moderate levels of extroversion displayed by ambivert personalities perform significantly better on both verbal and performance measures of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (Stough, Brebner, Nettelbeck, Cooper, Bates, & Mangan, 1996).

- Introverted learners use a greater range of metacognitive and cognitive strategies than extroverted learners. Naci-Kayaoglu (2013) investigated the link between extroversion and language-learning strategies. The results indicate that introverts consciously employ goal-oriented specific behaviors to ease the acquisition, retrieval, storage, and use of information for both comprehension and production and extroverted learners used more interpersonal communication strategies.

- Extroverts show superior performance in learning tasks when rewarded. Pickering, Corr, Powell, Kumari, Thornton, & Gray (1995) suggest that dopamine responsivity encourages sensitivity to rewards in extroverts, while introverts exhibit greater sensitivity to punishment.

Carl Jung’s Work on the Topic

The concepts of extraversion and introversion have been apparent in modern psychological theory for decades with popularization of the terms and acceptance by the psychology community largely attributed to the work of Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung.

According to this early work in the area, Jung (1921) posited that individuals hold one of two mutually exclusive attitudes with those being extraverted or introverted.

Jung suggested that an individual’s extraversion-introversion preference could be determined by the way in which individuals direct their “general interest” with extraverts focusing on the external and introverts focused internally.

Jung went on to broadly describe the difference in behavioral characteristics to highlight the distinctly separate attitudes.

According to Jung, the two types are “so different and present such a striking contrast that their existence becomes quite obvious even to the layman once it has been pointed out. Everyone knows those reserved, inscrutable, rather shy people who form the strongest possible contrast to the open, sociable, jovial, or at least friendly and approachable characters who are on good terms with everybody, or quarrel with everybody, but always relate to them in some way and in turn are affected by them.” (1921, para. 557).

Jung suggested that we each have a bias towards introversion or extraversion and that this tendency towards one or the other was universally determinable not only among the educated but in all ranks of society. For Jung, these tendencies can be discovered “among laborers and peasants no less than among the most highly differentiated members of a community.” (1921, para. 558).

Furthermore, Jung posited that given the apparently random distribution of attitude types, the general attitude type was not a product of a conscious or deliberate choice of attitude, suggesting instead an unconscious, instinctive cause with a biological precursor.

Jung described an extraverted individual as one who is orientated by objective data. Jung said that when an individual’s orientation to external objects and objective facts become the predominant drivers of behavior, the individual can be said to be extraverted.

On the other hand, the introverted attitude type belongs to an individual who, rather than being driven to action by external objects and an objective assessment of facts, is driven by subjective factors. Jung attributes the introverted attitude type as a tendency towards subjective determinants rather than as a failure to acknowledge the objective.

Jung regarded extroversion and introversion as the major orientations of personality.

These orientations were expressed through individual preferences for non-rational functions of sensation (our immediate experience of the objective world) and intuition (our perception of inner meanings), or rational functions of thinking (evaluation that is concerned with the truth or falsity of experience) and feeling (judging the value of things based on likes and dislikes).

In essence, Jung’s early work on the dichotomous nature of man suggested that extraverted individuals attributed higher weight to objective facts in determining actions while an introverted attitude type was biased towards basing decisions on subjective interpretations.

Other Introvert-Extrovert Tests, Scales, and Quizzes: A Look at the Validity

In psychology, the concept of validity refers to a test’s ability to measure what it is intended to measure (Kelly, 1927). If a test fails to relate to underlying theoretical concepts or predict future performances, its validity is certainly compromised. Consider the plethora of ‘personality quizzes’ you can find online. While some may be based on existing theories and tests, can you really be sure of their legitimacy?

Popular TED speaker and organizational psychologist, Adam Grant, developed the 10-question quiz ‘Are you extrovert, introvert, or ambivert?’ based on previous personality tests like the MBTI. On completion of the test, you will be given your extroversion score on a scale of 1-10 and provided some interesting information to assist your understanding of the results.

While this quiz is less detailed than others, it is easily accessible and a useful tool to help you recognize your personality type in relation to extroversion. Grant estimates that between 50% and 66% of the population are ambiverts, why not give this short quiz a try and discover where you lie on the introvert-extrovert spectrum.

Eysenck’s Personality Inventory (EPI) was Eysenck’s initial attempt to measure levels of extroversion and neuroticism through a series of yes and no questions. This was later developed into Eysenck’s Personality Questionnaire (EPQ).

Based on the initial EPI, the EPQ includes a further dimension of psychoticism and consists of 57 questions. The EPQ does have limitations in relation to other complete ‘personality tests’ considering it is built upon just three dimensions, it is a simplistic measurement scale.

The Big Five Personality Test is made up of fifty statements which are scored on a five-point scale from agree to disagree. This test is commonly used as a valid measure of the five broad dimensions that define human personality (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism).

The Quiet Introversion Questionnaire was developed by Susan Cain as a response to researcher dissatisfaction with the ‘extroversion ideal’ and society’s tendency to favor extroversion over introversion. The 20-item questionnaire measures personality traits such as preferences for solitude and for small scale social activities as a means to aid understanding of where individuals lie on the extroversion-introversion spectrum.

Introvert and Extrovert Relationships

Relationships between introverts and extroverts can be fraught with obstacles and misunderstandings. There is a whole world of literature with the sole purpose of helping one to understand the other.

The dichotomy of extroversion and introversion means the two have very different preferences when it comes to interacting with others. An extrovert might think nothing of picking up the phone to have a spontaneous chat with someone. However, if the person on the other end of the line is an introvert, it may well be considered completely inappropriate.

A conversation-loving extrovert can overwhelm an introvert with too much information. The overstimulated introvert can come across as disinterested when, in fact, they simply feel overloaded.

In relationships where one is extroverted and the other introverted, communication problems can be paramount with each person misunderstanding the other.

Consider an extrovert/introvert couple after a long day at work, introverts can find human interaction exhausting, preferring quiet after a day spent with others.

Extroverts – being energized by other people – are likely happy to continue socializing. While both have the capacity to exhibit outgoing, sociable, or unsociable behaviors, introverts and extroverts generally choose to seek out situations congruent with their personality type.

It’s not hard to see how this could be problematic if one wants to relax quietly at home while the other wants to go and socialize further.

We know that extroverts get their energy from external stimuli and love to talk, it may be difficult for an introvert to understand this. Rather than talking about things, introverts value time alone to process and formulate their thoughts. This can leave the extrovert seeing the introvert as aloof and standoffish while the extrovert is considered to be loud and overwhelming.

According to Diener, Larsen, & Emmons (1984), extroverts flourish when provided an abundance of social interactions; conversely, introverts prosper when able to withdraw from social situations if required.

Consider extroversion and introversion in the workplace. For extroverts, the hustle and bustle of a busy environment provide energy while being alone depletes it. The opposite is true for introverts, with distractions creating problems with concentration. It is easy to see how this can impact both productivity and create conflict between the two personalities.

When dealing with conflict, the extrovert and introvert have very different approaches. Oftentimes, introverts are less assertive, less willing to compete and avoid conflict altogether. According to (Kilmann & Thomas, 1976) individuals who exhibit high extraversion tend to be more likely to confront conflict head-on with an integrative and assertive approach.

While it may appear that relationships between extroverts and introverts are doomed to fail, it’s simply not the case. The primary cause of conflict between the two is a lack of understanding on each side. Fortunately, we can overcome this apparent mismatch.

5 Recommended Books

With such an intriguing subject, one would want to read more than just a blog post. To help you out, below is a selection of five recommended books on the topic.

1. The Genius of Opposites: How Introverts and Extroverts Achieve Extraordinary Results Together – Jennifer B. Kahnweiler

At the heart of The Genius of Opposites is the idea that while relationships between introverts and extroverts can be tenuous, the two can work together with incredible results.

Through discussions on introvert-extrovert partnerships, Kahnweiller provides a 5-step process to set these pairs up for success and avoid a break down by learning from the other and developing new skills.

Find the book on Amazon.

2. Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking – Susan Cain

In Quiet, Susan Cain discusses how our lives are driven by whether we are an introvert or an extrovert.

Written as a response to what Cain describes as the ‘extrovert ideal’ – the omnipresent belief that the ideal self is gregarious, alpha and comfortable in the spotlight – Quiet looks at how the brain chemistry of introverts and extroverts differs, and the ways in which introverts are often misunderstood.

The book also contains helpful tools and techniques that allow the introverts among us to better understand themselves and take full advantage of their strengths.

Find the book on Amazon.

3. Success as an Introvert for Dummies – Joan Pastor

Success as an Introvert is like a survival manual for introverts. In her work, Pastor offers practical tips on how to become a confident public speaker, an effective team leader, and succeed as an entrepreneur.

There are also chapters on finding personal happiness and advice on how to be supportive of introverted friends and children.

Find the book on Amazon.

4. Me, Myself, and Us: The Science of Personality and Well-Being – Brian R. Little PhD

Me, Myself, and Us examines personality as a sum of its components, including aspects of extroversion and introversion.

Little shares recent data and insights about who we are, why we act the way we do, and how we can best flourish in light of our personality.

Me, Myself, and Us also considers what our personalities portend for our health and success, and the extent to which our well-being depends on the personal projects we pursue.

Find the book on Amazon.

5. The Science of Introverts (And Extroverts and Everyone In-Between): Master Your Personality, Amplify Your Strengths, Understand People, and Make More Friends – Peter Hollins

The Science of Introverts provides a simplified yet thorough look at introversion and extroversion in everyday life.

Psychologist, Peter Hollins, gives tips on how to thrive socially, harness your personality for success, and how to capitalize on your unique strengths.

Find the book on Amazon.

5 Interesting TED Talks

Who are you really? The puzzle of personality – Brian Little

Why we need introverted leaders – Angela Hucles

Blueprint for a quiet revolution – Susan Cain

Introvert, extrovert, or ambivert – Stephanie Maggio & Ghilene Joseph

In defense of extroverts – Katherine Lucas

A Take-Home Message

Regardless of where you fall on the extroversion spectrum, there is no ‘better’ personality. If we work towards understanding our own motivations and energy we, in turn, gain a greater understanding of the motivations and energy of those around us.

Many of the conflicts between extroverts and introverts can be resolved or avoided altogether. Simply being aware that there is a distinction can be enough to change how you think about and approach those whose behavior seems alien to yours.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

- Abernethy, E.M. (1938). Dimensions of Introversion-Extroversion. Journal of Psychology, 6, 217-223

- Akert, R.M. & Panter, A.T. (1988). Extraversion and the ability to decode nonverbal communication. Personality and Individual Differences, 9, 965-972.

- Amichai-Hamburger, Y., Wainapel, G., & Fox, S. (2002). “On the Internet no one knows I’m an introvert”: Extroversion, neuroticism, & Internet interaction. Cyber Psychology & Behavior, 5, 125-128.

- American Trends Panel. (10 Dec. 2015) “Rating Personality Traits.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, American Trends Panel. Retrieved from: www.pewinternet.org/2015/12/11/public-interest-in-science-and-health-linked-to-gender-age-and-personality/pi_2015-12-11_science-and-health_2-01/.

- Belojevic, G., Slepcevic, V. & Jakovljevic, B. (2001) Mental performance in noise: the role of introversion. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21, 209–213.

- Beukeboom, C.J., Tanis, M., & Vermeulen, I.E. (2012). The Language of Extraversion: Extraverted People Talk More Abstractly, Introverts Are More Concrete. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 32, 191-201.

- Cattell, R.B. (1965). The Scientific Analysis of Personality. NYC, NY: Penguin Group

- Codish, D. & ravid, G. (2014). Personality-based gamification – Educational gamification for extroverts and introverts. Proceedings of the 9th Chais Conference for the Study of Innovation and Learning Technologies. Raanana: The Open University of Israel.

- Conklin, E.S. (1923) The definition of Introversion, Extroversion and Allied Concepts. Journal of Abnormal Psychology and Social Psychology 17, 367-382

- Diener, E., Larsen, R. J., & Emmons, R. A. (1984). Person Situation interactions: Choice of situations and congruence response models. Journal of personality and social psychology, 47, 580.

- Eysenck, H.J. (1967). The Biological Basis of Personality. C.C. Thomas: Springfield.

- Eysenck, M.W. (1982) Attention and Arousal. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Fischer, H., Wik, G., & Frederikson, M. (1997). Extraversion, neuroticism and brain function: A pet study of personality. Personality and Individual Differences. 23, 345-352

- Freeman, D. (2008). The MBTI instrument in Asia. Singapore MBTI Asia Conference. Singapore.

- Freud, S. (1920). A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. Translated by Stanley Hall, G. New York: Boni and Liveright. Retrieved from:. www.bartleby.com/283/.

- Guilford, J. P., & Guilford, R. B. (1936). Personality factors S, E, and M, and their measurement. The Journal of Psychology, 2(1), 109-127.

- Harbaugh, E.R. (2010). The effect of personality styles (level of introversion-extroversion) on social media. Elon journal of undergraduate research in communications, 1, 70-86.

- Heidbreder, E. (1926). Measuring introversion and extroversion. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 21(2), 120–134.

- Heaton, A.W. & Kruglanski, A.W. (1991). Person Perception by Introverts and Extraverts Under Time Pressure: Effects of Need for Closure. Personality and social psychology bulletin, 17, 161-165.

- Johnson, D.L., Wiebe, J.S., Gold, S.M., Andreasen, N.C., Hichwa, R.D., Watkins, G.L., & Boles-Ponto, L.L. (1999).Cerebral blood flow and personality: a positron emission tomography study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 252-257.

- Judge, T. A., Higgins, C. A., Thoresen, C. J., & Barrick, M. R. (1999). The Big Five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Personnel Psychology, 52, 621-652.

- Khalil, R. (2016). Influence of extroversion and introversion on decision making ability. International journal of research in medical sciences, 4.

- Kilmann, R.H. & Thomas, K.W. (1975). Interpersonal Conflict-Handling Behavior as Reflections of Jungian Personality Dimensions. Psychological Reports, 37, 971-980.

- Lei, X., Yang, T. & Wu, T. (2015). Functional neuroimaging of extraversion-introversion. Neuroscience Bulletin, 31, 663.

- McAdams, D. (2017, January 12). The two kinds of stories we tell about ourselves [Interview by E. Smith]. Retrieved March 20, 2019, from https://ideas.ted.com/the-two-kinds-of-stories-we-tell-about-ourselves/

- Myers, I. B., McCaulley, M. H., Quenk, N. L., & Hammer, A. L. (1998). MBTI Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (3rd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press

- Naci-Kayaoglu, M. (2013). Impact of extroversion and introversion on language-learning behaviors. Social behavior and personality, 41, 819-826.

- Noman, R. (2016). Influence of extroversion and introversion on decision making ability. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 1534-1538. 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20161224.

- O’Connor, P.J., Gardiner, E., & Watson, C. (2016). Learning to relax versus learning to ideate: Relaxation-focused creativity training benefits introverts more than extraverts. Thinking Skills & Creativity, 21, 97-108.

- Pickering, A.D., Corr, P.J., Powell, J.H., Kumari, V., Thornton, J.C., & Gray, J.A. (1997). Individual differences in reactions to reinforcing stimuli are neither black nor white: To what extent are they Gray? In H. Nyborg (Ed.), The scientific study of human nature: Tribute to Hans J. Eysenck at eighty. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V.

- Jung, C.G. (1921). Psychological Types. In G. Ardler & R.F.C. Hull (Eds.). The Collected Works of C.G. Jung. Complete Digital Edition. Retrieved from https://www.jungiananalysts.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/C.-G.-Jung-Collected-Works-Volume-6_-Psychological-Types.pdf

- Richard, L. (1993). The Lawyer Types. The ABA Journal, July.

- Roback, A.A. (1927) The Psychology of Character, With a Survey of Temperament. Journal of Philosophical Studies, 3, 123

- Rutter, D. R., Morley, I. E. & Graham, J. C. (1972). Visual interaction in a group of introverts and extraverts. European Journal of Social Psychology, 2, 371-384.

- Scherdin, Mary Jane (1994) Vive la différence: Exploring librarian personality types using the MBTI. In Discovering Librarians: Profiles of a Profession, 125–156. Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries, American Library Association.

- Stough, C., Brebner, J., Nettelbeck, T., Cooper, C.J., Bates, T. & Mangan, G.L. (1996), The relationship between intelligence, personality and inspection time. British Journal of Psychology, 87: 255-268.

- Suslow, T., Kugel, H., Reber, H., Dannlowski, U., Kersting, A., Arolt, V., Heindel, W., Ohrmann, P., & Egloff, B. (2010). Automatic brain response to facial emotion as a function of implicitly and explicitly measured extraversion. Neuroscience, 167, 111-123.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (50)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (33)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

Hiiii, can you tell me a weakness of this theory?

Hi Geneen,

Thank you for your question. It depends on which theory you aim to understand introversion and extroversion through, as this dichotomy appears in several theories of personality. For instance, if you’re considering introversion-extroversion through the lens of Myers-Briggs, this framework has quite a few well-documented weaknesses (you can read more about those here). The Big-5 model also has its own criticisms (see here).

Hope this helps!

– Nicole | Community Manager