Neurodiversity in the Workplace – A Strengths-Based Approach

The first step toward building a neuroinclusive workplace is raising employees’ awareness of neurodiversity as part of employee DEI training (Doyle, 2020).

Understanding trauma-informed perspectives on neurodiversity

Despite the well-meaning intentions often stated in an organization’s HR policies, neurodivergent people still face ignorance and stigma in their workplaces (Mellifont, 2020).

Many neurodiverse employees will have been misunderstood, bullied, excluded, and discriminated against at school, in their family, by their peers, at college, and at work.

This means almost all neurodiverse workers will have to manage trauma responses at work as well as their differences from the neurotypical majority (Lively, 2023). In addition, many will be very hard on themselves after internalizing the idea that something is wrong with them (Aherne, 2023).

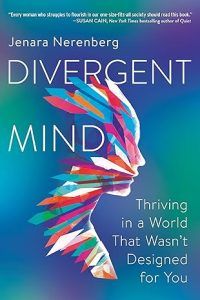

Being constantly misunderstood leads to feeling unsafe and having a dysregulated nervous system. This has somatic as well as psychological consequences. Neurodiverse people are more likely to experience migraines, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, anxiety, and depression (Nerenberg, 2020).

The higher incidence of coexisting conditions is not due to deficits of the neurotype, but struggles with trauma responses triggered by an ableist, unsafe, and dysregulated environment (Mellifont, 2020).

Neurodistinct people may be treated unfairly if they do disclose their neurotype, due to unconscious bias based on unspoken but powerfully operational stereotypes (Lively, 2023). For example, the idea that people with autism are nonverbal and antisocial, or that ADHDers are chaotic fidgets that can’t stop talking. These are stereotypes based on deficit-based thinking about neurodiversity that are not trauma informed (Nerenberg, 2020).

Recent lived experience-led research has proposed that many of the stereotyped “symptoms” associated with certain neurotypes are in fact trauma responses (Strang et al., 2019).

For example, autistic withdrawal, meltdowns, and ADHD over-explaining and oversharing may be self-regulation strategies that aim to make an unsafe environment safer. In other words, they are trauma responses. However, they are often deemed “symptoms” of autism or ADHD (Aherne, 2023). These behaviors are likely to lessen or disappear in neuroinclusive environments.

Social inclusion in the neurodiverse workplace

When offering neurodiversity awareness training at work, it is best to approach the topic as analogous to biodiversity in nature. The wider our variety of human neurotypes in the workplace, the better off the organization (Aherne, 2023; Armstrong, 2010; Doyle, 2020; Silberman, 2013).

Neurodiversity awareness training is crucial for promoting social inclusion at work and necessitates a strengths-based approach to neurodiversity in the workplace (Lively, 2023).

Strengths of a neuroinclusive workforce

A neuroinclusive workforce includes a wider range of strengths, talents, and abilities than a less varied employee profile (Doyle, 2020). Embracing neurodiversity in the workplace enhances an organization’s creativity, innovation, productivity, and resilience (Cognassist, 2024).

For example, consider this quote from James Mahoney, executive director and head of Autism at Work at JPMorgan Chase (Eng, 2018, para. 12).

“Our autistic employees achieve, on average, 48% to 140% more work than their typical colleagues, depending on the roles. They are highly focused and less distracted by social interactions. There’s talent here that nobody’s going after.”

You can find out more about how to recruit and maintain a neuroinclusive workforce by taking the Neurodiversity Certified Training course offered by neuroinclusion specialists Cognassist. You can also download a free PDF of workplace adjustments to support neurodiversity.

Finally, it’s always inspiring to hear a real-life success story to illustrate a point. I urge you to take a look at this brilliant TEDx talk, “Rebranding The Brain: Neurodiversity at Work,” by Dave Thompson. Thompson is neurodistinct himself and supports companies in becoming more neuroinclusive.

This section describes the most common types of neurodivergence and their respective strengths and challenges.

This section describes the most common types of neurodivergence and their respective strengths and challenges.